Maison Zilveli

Architect: Jean Welz

Year of completion: 1933

Location: Paris, France

Demolished

Latest update 20 January 2023

Jean Welz

A leading painter still highly regarded in South Africa, Jean Welz was an economic emigre from Europe on the eve of WWII. His prior architectural career has been virtually unknown until a string of discoveries unfolded for author and filmmaker Peter Wyeth over eight years, allowing him to narrate this amazing true tale of genius.

Born in 1900 and trained in ultra-sophisticated, but conservative Vienna, Welz was sent to Paris for the 1925 Art Deco exhibition by his influential employer, renowned architect Josef Hoffmann. There he met preeminent modern architects Le Corbusier and Adolf Loos. The latter employed him to assist in building a house for the founder of Dada, Tristan Tzara. They all mixed in avant-garde circles at the Café du Dôme in Montparnasse along with Welz’s classmate from Vienna, later Chicago-based architect Gabriel Guevrekian; Welz’s future employer Raymond Fischer, whose archive was mostly destroyed by Nazis; and photographer André Kertész.

In his book The Lost Architecture of Jean Welz, (November 2021) author Peter Wyeth retrieves stories, letters, portfolios, and photographs through Welz’s South African family archive, generations after Welz’s death that unravel his heroic designs, his stunning built critique of Corbusier’s “Five Points of Architecture,” a gravestone for Marx’s daughter, and the many ways that Welz disappeared amongst his collaborators, intentionally and not. This account of why Jean Welz did not become a famous name in architecture takes us through his brother’s Nazi-dealings, illness, betrayal, self-destruction, Apartheid, and an uncompromising artist’s vision at the same time sifting through significant, literally-concrete evidence of Welz’s built projects and visionary designs.

Maison Zilveli

The two storey home sits on the top of a hillside on stilts, in a narrow strip of land just 6 meters by 30 meters, and suspended five meters above the ground. It is rectangular shaped measuring 20 meters long by 4.5 meters wide and hovers over the cliffside with one window that frames the view over Montmartre and the basilica of Sacre Coeur and another facing south with a view of the Eiffel Tower. It included a balcony that was subsequently destroyed, and the interiors were divided into split-level spaces according to functional hierarchy.

Threat

The house had very little repair or maintenance over its life, and as of January 2020 it is wrapped 'Christo' style by the Town Hall against bits falling off. It went to auction three times, the first buyer failed to pay, by the third it was said to be in the hands of Jean-Paul Goude, eminent image-maker (eg Grace Jones) and graphic designer who was rumoured to want it as a gallery for his art work (he lives next-door but one). The future of this avant-garde masterpiece of the architect Jean Welz remains in the balance but Goude's creative background may make him sensitive to Welz's striking achievement and insist on a painstaking restoration respecting the fabric and keeping it virtually 100% original.

Latest News

Le Monde, 9 April 2021

Le photographe Jean-Paul Goude doit démolir sa villa à Paris achetée pour 22 millions d’euros

A deserted Paris house holds the mystery of a brilliant Viennese modernist who worked alongside Corbusier and Loos before vanishing.

The below article was previously published in the Twentieth Century Society’s C20 Magazine, issue 3 2013. www.c20society.org.uk

Peter Wyeth discovers an important modernist house in need of urgent repair

Imagine coming across the most radically modernist house you have ever seen, in the middle of Paris. It’s deserted and falling into ruin, its interior unchanged since it was built eighty years ago. Perched on a hillside with a distant view of Montmartre, it is today a sad sight: its street façade cracked, the elevations leaning alarmingly and the steel-framed windows askew. The house is supported – rather precariously these days – on cruciform pillars in reinforced concrete, rising almost five meters from the ground.

With its pilotis and its long façade at right angles to the street, the casual eye might attribute the house to an amateur Le Corbusier. In its present state, it is an image of modernism gone shabby – or moche (ugly), as an elderly neighbour described it, ironically referring to the house as ‘Le Chateau’ – but a monochrome photograph of the building when it was built presents a very different image.

Jean Welz

We can learn more about the house by peeling back the historical layers to 1918 Vienna, when a young would-be architect arrived there to study under Josef Hoffmann but soon fell under the spell of Adolf Loos, arch-critic of Hoffmann. That student, Jean Welz, would go on to become one of South Africa’s leading painters, and by the time of his death in 1975 his architectural past was almost forgotten. Even the house in question is listed in the local town hall under the name of another architect.

There is a remarkable terrace of three attached modernist houses just outside the Paris périphérique, no 8 is by Mallet-Stevens, no 6 by Le Corbusier (Maison Cook), and no 4 is credited to Raymond Fischer (Maison Lubin) but according to Welz’s family, that house should be attributed to him. Welz worked for Mallet-Stevens and then with Loos on a house in Paris for Tristan Tzara, before becoming chef de cabinet in the Fischer practice. Welz was also a friend of Le Corbusier, who wrote him a letter of recommendation when he left for South Africa. Two houses were credited to him in the leading French magazine of Modern architecture of the time, L’Architecture d’Aujourd’hui. The first, in 1931, has a short text by Fischer praising its ‘maison minimum’ contribution. The second, dated 1933, is credited to Weltz (sic). This is the radical house shown in these photographs, Maison Zilveli.

Modernist language

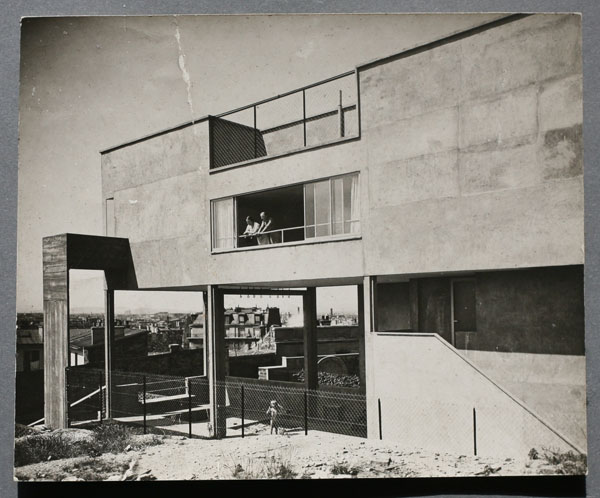

The site is an unstable hillside, created from the waste extracted to build the Parc des Buttes Chaumont in 1867. The most distinctive aspect of the site is hardly visible from ground level, but is perfectly served by Welz’s house on stilts, for few houses could claim such views. One large window faces west towards Montmartre and the basilica of Sacré Coeur, while the other faces south, with a view of the Eiffel Tower. Welz conceived a long box 20 meters by 4.5 meters, stuck five meters in the air and high enough to see beyond the building-line of its brick-built neighbours.

Apart from the priceless views, the budget must have been kept to an absolute minimum, as the house is very cheaply constructed. The street elevation exceeds the plainness of his master Loos, and must have been a slap in the face of its bourgeois neighbours. The long south facade bears comparison with the Villa Savoye, but it was neither skimmed nor painted, and it does not hide the fact that it was made in sections. It was topped by an extraordinary balcony (destroyed by the local prefecture without objection from the Architectes des Bâtiments de France) with its 10 cm beton brut supporting blade bearing the marks of its wooden shuttering construction. This is perhaps the first such finish in the history of Modern architecture, fifteen years before Le Corbusier’s Unité d’Habitation in Marseilles and forty years before Denys Lasdun’s National Theatre.

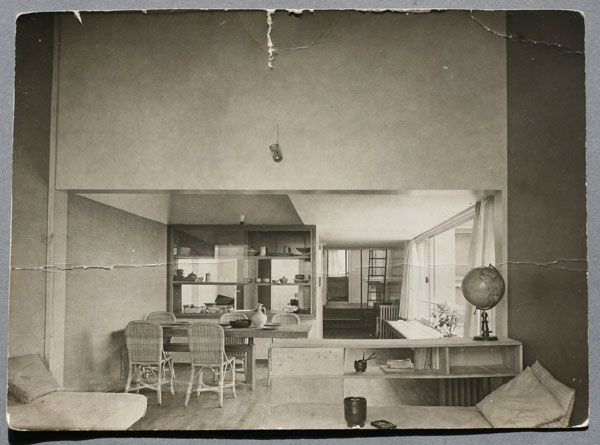

That striking balcony had a built-in desk and seat, an outside office facing Sacré Coeur - echoing the view from the big ‘l’Esprit Nouveau’ end window. Loos’s Raumplan concept held that interiors should be divided into split-level spaces according to their functional importance, and his influence on Welz is clear, with three levels on the main floor alone. Altogether, the house is an oddity, but one intimately influenced by the heroic era of Modern architecture, while also making a highly distinctive contribution to it.

Saving Maison Zilveli

To try to save Maison Zilveli I have worked with a Parisian architect who brought in a top engineer to survey the structure. He visited several times and drew up recommendations to stabilise the ground beneath and the reinforced concrete above. The architect both devised a budget for the engineering work and the restoration project and researched a Foundation to which the house can be donated as part of a cultural project I devised. Les Modernistes Disparus would document the diaspora of modernist artists in every art who left Paris in the 30s either through the Great Crash of 1929 or the rise of fascism. Conserving the patina of the building is a major priority and the restored house would be a base for small exhibitions and research presentations across the modernist arts of the 30s, and a tribute to the rigorous creative imagination of Jean Welz.

Peter Wyeth

Peter Wyeth has been making films since the 1970s, including several with the Arts Council of Great Britain, one of which, about a modernist block of flats in London, inspired by Hokusai (“12 Views of Kensal House”) was runner-up for best documentary. He started a forgotten film-mag North by North West, and in 1994 directed “The Diary of Arthur Crew Inman,” based on the 17-million-word and longest diary in America and named a London Times “Film of the Week.” From 1999–2003, Wyeth was head of the film school at University of the Arts London, where he worked for ten years and set up the student channel Xplore.tv. His short film “Pane” won a Turner Classic Movies award in 2003. His book The Matter of Vision: Affective Neurobiology and Cinema was published by Indiana University Press in 2015 (in the UK by John Libbey Media) and over the past six years he has written two dozen articles on architecture and design for The Modernist, and is working on a film set in Sicily. He has three children and a grandson, and lives in London and Paris with his wife, whom he married in the glorious Town Hall of the 19th arrondissement of Paris: a stone’s throw from Jean Welz’s Maison Zilveli.

Image source renderings of the future villa Zilveli in slideshow, after complete reconstruction: Lankry architectes.

Maison Zilveli, November 2019.

Maison Zilveli, November 2019.

Maison Zilveli in 2013.

Maison Zilveli in 2013.

The original fitted table has been pulled from the wall by burglars but proved too heavy to remove.

The original fitted table has been pulled from the wall by burglars but proved too heavy to remove.

Loosian plainness: the street facade in 2013.

Loosian plainness: the street facade in 2013.

The fitted table inside was made by a Greek sculptor friend.

The fitted table inside was made by a Greek sculptor friend.

House on stilts: on completion in 1933. Note the sandpit next to the small child.

House on stilts: on completion in 1933. Note the sandpit next to the small child.

Literature

The Lost Architecture of Jean Welz

Peter Wyeth

2021

Buy the book

News Archive

Le Monde, 26 June 2019

A Paris, Jean-Paul Goude sauve le squat de « Vernon Subutex »

Maison Zilveli

Jean Welz

1933, France